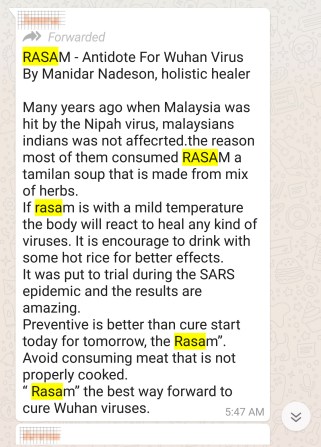

Not long ago, a close relative of mine forwarded a message on a WhatsApp family group that claimed rasam cures coronavirus. Rasam, a soup-like concoction of herbs, tamarind juice, and lentils, is the cultural equivalent of chicken soup (but vegetarian) in South India, where I am from. Normally, I’d search on the internet to check if a post that seemed suspicious was false, like one I saw that claimed that a well-known British writer had endorsed Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. (He didn’t.) But in this case, I didn’t have to google anything to know this was factually incorrect. As a friend pointed out on Twitter, rasam may cure homesickness and winter blues, but it is no cure for coronavirus.

When I politely pointed out that they might have sent a fake post, the sender retorted, “It has pepper and jeera [cumin] and it will build up your immunity.” All I could do was  .

.

WhatsApp messages about supposed cures for the coronavirus. (Some personal details have been obscured.)

Sinduja Rangarajan

A few days later, another relative forwarded a post in WhatsApp with “facts about the coronavirus” supposedly put out by UNICEF. While most of the “facts” were innocuous, including instructions to vigorously wash hands, some were unproven, like a claim that the virus can’t survive at high temperatures. It turns out the post didn’t come from UNICEF at all. When my husband pointed out that the post seemed inaccurate, the relative replied, “But what’s the harm in following all this?” unconcerned by fake news simply because it was fake.

Misinformation on WhatsApp isn’t unique to my family or even my country. The app, which is owned by Facebook, is one of the world’s most popular messaging platforms, particularly in countries where internet infrastructure is sparse and underdeveloped.

UNICEF has debunked this post doing rounds in WhatsApp groups.

With more than 2 billion users, the platform has regularly been a conduit for fake news and misinformation. In India, fabricated videos of child kidnapping gangs on WhatsApp have led to lynchings of innocent people. In Brazil, the rapid spread of misinformation threatened the fairness of the 2019 presidential election. And amid the coronavirus pandemic, WhatsApp has become conduit for fake cures and conspiracy theories about coronavirus.

AFP FactCheck, the fact-checking arm of Agence France Presse, has already identified and debunked 140 different myths circulating around WhatsApp. No, cannabis can’t cure coronavirus; no, Zimbabwe doesn’t have any COVID-19 cases yet; no, Chinese people are not converting to Islam because of the outbreak.

These kinds of posts have been shared in private chat groups from Indonesia to Nigeria to Sri Lanka. AFP FactCheck flagged a post from Nigeria about the antimalarial drug chloroquine being “a cure for the Coronavirus,” prompting an official investigation in the United Kingdom into a website that was selling the drug. (At a press conference Thursday, President Donald Trump suggested that the Food and Drug Administration had approved chloroquine as a COVID-19 treatment. In fact, the drug needs to be tested to see if it is effective against the coronavirus.) A Twitter search for the keywords “Coronavirus WhatsApp” led me to even more obviously false theories such as how pharmaceutical companies have engineered the pandemic to more herbal cures and misinformation about the virus.

We are concerned about #coronavirus misinformation and rumours attributed to UNICEF being circulated through social media and messaging platforms such as WhatsApp and Viber in #Nepal. For accurate information on #covid19, please visit https://t.co/iF3vZIZahh #covid_19 #corona pic.twitter.com/BVsb2DAcgm

We are concerned about #coronavirus misinformation and rumours attributed to UNICEF being circulated through social media and messaging platforms such as WhatsApp and Viber in #Nepal. For accurate information on #covid19, please visit https://t.co/iF3vZIZahh #covid_19 #corona pic.twitter.com/BVsb2DAcgm

— UNICEF Nepal (@unicef_nepal) March 5, 2020

“Constant sex kills coronavirus,” reads the text on what seems to be a screenshot of a @CNN news report, posted on #Facebook & #WhatsApp.

It shows US journalist @CNN anchor, @wolfblitzer, & the network’s logo.

The screenshot is FAKE.

Read: https://t.co/9LQyHyg8yt

— AfricaCheck_NG (@AfricaCheck_NG) March 6, 2020

Anybody else tired of the “how to stop corona virus” messages in the Nigerian family Whatsapp groups?

One Aunty said drink hot water. Another said corona cannot enter Ibadan.

— Flex God Daps (@FlexGodDaps) March 11, 2020

WhatsApp is different from other social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and Instagram because it is a messaging app meant for staying in touch with friends and family. One of its biggest sells is privacy: You can’t join a group unless someone within it adds you. Groups have no public link and there is no publicly available data on how many exist, who’s in them, or what their average size is. In that sense, WhatsApp is like a black box. The company says that the majority of these groups are small (10 members or less) and 90 percent of the messages are sent directly from members (rather than forwards). Yet the app is known for its large groups where users send forwarded jokes, images, and multimedia messages.

Harsh Taneja, a professor of advertising at the College of Media at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, says WhatsApp is susceptible to misinformation because of it’s a “large and complex web of invisible networks where a lot of things circulate in specific circles of communication which we cannot track.” He says, “If I come across a bizarre post on WhatsApp, I immediately google and see that the New York Times or Snopes have debunked it.” But many WhatsApp users rely on it as a primary source of information. “WhatsApp means the internet to these users and internet means WhatsApp.”

WhatsApp is also unique in that it offers end-to-end encrypted service, which means only the senders and recipients—not the platform itself—can see the content of messages. While encryption makes the platform secure and protects privacy, can be a double-edged sword. Governments have asked WhatsApp to break its encryption to aid with criminal investigations; so far, the platform has refused. But researchers, journalists, and fact checkers say that encryption makes it impossible to track the source of fake or misleading messages.

Unlike Facebook, which has implemented protocols to reduce, retract, and inform users about the spread of misinformation, WhatsApp cannot algorithmically track the origin of viral messages or curb them. But it has taken some steps to stem the flow of unreliable information. In 2018 it started tagging forwarded messages as “forwarded,” which it claims has reduced the spread of forwarded messages by 25 percent. It has capped the maximum group size at 256 members and limited the number of chat groups a user can forward the same message (5 chats).

But data and computer scientists say just limiting forwards is not enough. Researchers from Brazil’s Federal University of Minas Gerais and Massachusetts Institute of Technology found that depending on the viral nature of content, forwards still have potential to reach many users quickly. They proposed that WhatsApp should quarantine and temporarily restrict virality features for users suspected of spreading misinformation and content on their platform.

In an article for the Columbia Journalism Review, Taneja and Himanshu Gupta, a digital marketing professional, proposed ways for WhatsApp to control the spread of fake posts without breaking encryption. Even though WhatsApp can’t read encrypted messages, the researchers hypothesize that it may be able to trace the source of rogue messages and flag them as suspicious through other data it tracks. “WhatsApp is very aware of their disinformation problem, but they have done little at scale from a technical point of view,” Taneja said.

A Facebook spokesperson disputed the researchers’ assumptions in an email. “We do not have the ability to trace or block a specific piece of content on a platform wide basis, period,” he told me. (The spokesperson told me the company had not been contacted by the researchers before publication to his knowledge; the authors of the article showed me emails they had sent to the same spokesperson I was in contact with.)

Most of WhatApp’s efforts to curb the spread of misinformation have focused on partnering with fact-checking organizations and governments. Brazilian journalists used a WhatsApp enterprise account where users could flag suspected forwards so journalists could review and debunk them. The team replied to the person who sent the original message with a simple note or a link to the published article on the topic. WhatsApp has replicated this kind of partnership with fact-checking organizations in India, Brazil, and Nigeria, according to the spokesperson. It has also organized media literacy campaigns with the message of “share joy, not rumours” in countries such as India. With respect to the coronavirus, it said it has been partnering with governments in Singapore, Israel, Indonesia, and South Africa by providing them with WhatsApp business accounts that users can report suspicious posts to.

For now, the onus of keeping WhatsApp clean largely falls on conscientious users reporting fake content to governments and fact-checking organizations. While most suggestions to stop the spread of misinformation on WhatsApp have focused on technical solutions, little has been written about the cultural and social dynamics that make it difficult to control the spread of fake forwards.

It’s awkward to tell your relatives that their posts are factually incorrect, especially in front of other family members. It’s even harder in cultures where elders are supposed to be unquestionably respected. When I talked to a friend on Twitter about this, she wrote back, “I’m the asshole for debunking ‘salt gargle and homeopathy cures corona’ fwds.”

When I pointed out that the British writer never said those wonderful things about Modi, a relative defended the post by telling me that we were just sharing things for fun. “This is all just a timepass,” they said. Another sent me a private message on “how to be a positive journalist.” WhatsApp is a source of distraction and comfort during a difficult time, but it’s harmless only until it’s not.

Read more: motherjones.com