One of my favorite short films of all time wasn’t actually written by a human. It was written by a neural network named Benjamin, which was fed a lot of science fiction movies and then asked to write its own. Impressive, right?

The thing is: the movie is terrible. The dialogue makes sense, if you read each line on its own. But together? Together it’s just nonsensical—in the most entertaining way.

That’s great news for me, as a writer. Though outlets like the Washington Post have had some success with bot-driven sports journalism, I probably won’t be automated out of a job any time soon.

For other workers, though, it’s a fair question: “Will robots take my job?”

What counts as a robot?

When we talk about robots taking people’s jobs, what we’re actually talking about is automation more broadly. Only in some cases (like a car assembly line) does this involve literal, physical robots. This type of automation is called mechanical automation, and it’s been around for a while; General Motors installed its first assembly-line robot all the way back in 1961.

But there’s a different kind of automation making headlines recently: software automation (also known as process automation or work automation). It involves using code to automate tasks that humans would otherwise have to do, like creating an invoice in an accounting program.

You’ve experienced this type of automation already. Ever received a marketing email with a promo code, enticing you to make another purchase? Most companies use marketing automation software to send these emails, because it’s more efficient than doing it manually.

So how will automation affect jobs?

It can be tempting to look at the headlines surrounding automation and think we’re heading for some sort of jobless apocalypse.

But like most things, the reality is a bit more nuanced.

First, the bad news: low-skill jobs are pretty easy to automate away. According to a 2019 Brookings Institute report, automation will have the greatest effect on jobs where 70% of the responsibilities are “predictable physical and cognitive tasks.”

Outside of an office environment, these jobs are things like retail employees and warehouse workers, which companies like McDonald’s have famously experimented with automating in recent years.

Inside an office, though, low-skill jobs still exist, and the consensus is that they’re vulnerable to automation. These are jobs like data entry, filing, and document review—and in many cases, companies have already adopted automation to do them. Over the past few years, large law firms and consultancies like Deloitte have embraced automated document review and discovery, tasks that used to be done by humans.

But here’s where it gets a little tricky: repetitive, routine work isn’t limited to low-skill jobs. It also affects middle-skill workers, making them somewhat vulnerable to automation as well.

In fact, a 2017 report from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) found that across its 36 member nations, the share of workers in middle-skill jobs fell by 9% between 1995 and 2015. And this drop is partly attributable to automation.

Michael Chui, a McKinsey partner specializing in the impact of technology on business, writes:

Collecting data, processing data, office-support jobs, processing financial and other transactions—that’s very predictable work […] And even though it’s not physical work, it’s predictable work. On balance, we would likely see less of that, particularly when the technology reaches a stage at which it is lower-cost than deploying human labor for those activities.

In other words, as automation technology becomes cheaper than paying a human to do the same job, companies will scale their use of automation—and they’ll start with roles that involve a lot of repetitive work.

Okay, but you said there’s some good news

Now, the (relatively) good news: Complex tasks that require creativity and other forms of higher-order thinking are currently super difficult to automate. That’s because you need cognitive technology like artificial intelligence (AI) and automation together—also known as intelligent automation. And there’s a lot that AI just can’t do well, currently.

For example, AI is pretty good at identifying lung cancer compared to human doctors. But almost no one can imagine a scenario in which AI takes a leading role in patient treatment.

There are a few reasons for that, including the fact that AI lacks the sort of social intelligence and human warmth that patients expect from physicians. But there are also significant concerns about whether cognitive technologies can make ethically appropriate decisions—just look at the intense debate over how self-driving cars should behave when faced with difficult moral choices.

Additionally, it’s widely accepted that AI can reflect and even amplify human biases. Concerns about bias in cognitive technology can make many companies reticent to use it for complex office tasks like hiring, where biased decision-making can run afoul of the law. A couple years ago, for example, Amazon’s AI-driven internal hiring tool learned to overwhelmingly preference white men over other candidates. It was so problematic that the company eventually scrapped it.

There’s also a shortage of automation and AI talent, which makes it difficult for companies to scale their use of these technologies. A 2018 Capgemini survey indicated that though 84% of organizations are ideating, testing, or have deployed one or more automation use cases, only 16% have implemented multiple use cases at scale. The biggest reason they’re struggling? 57% say it’s a lack of talent skilled in automation technologies.

Of course, this might change quickly. Depending on the pace of automation development—which no one can seem to agree on—we could see some higher-order tasks being automated in the not-so-distant future.

You might not lose your job, but it’ll probably change

Taken together, all of these challenges mean that highly skilled jobs are a lot further away from being fully automated than you might initially think. But just because robots won’t take your job doesn’t mean your job won’t change.

In fact, it probably already has.

Think about your day-to-day work. You’re not doing everything by hand. If you work in marketing, for example, you don’t manually download leads from top-of-funnel sources like landing pages and manually export them into your email marketing app. It just happens—automatically.

Across a wide range of departments and industries, automation has already shifted what lots of knowledge worker roles entail. Many jobs now focus more on creativity, decision-making, and other forms of higher-order thinking. The World Economic Forum (WEF) and other experts have dubbed this shift the “Fourth Industrial Revolution”:

[It] represents a fundamental change in the way we live, work and relate to one another. It is a new chapter in human development, enabled by extraordinary technology advances commensurate with those of the first, second and third industrial revolutions.

In other words, automation is bringing big changes to the way people work. In terms of scale, they’re similar to the changes society experienced about 100 years ago with the advent of the assembly line, electricity, and industrialization.

So what can most knowledge workers expect?

By 2022, the WEF predicts that 62% of an average business’s data processing, information search, and information transmission tasks will be performed by machines—compared to 46% today. Machines will also do more of traditionally human-based tasks like communication, management, and decision-making, though to a lesser extent.

In other words, your work is likely to be less repetitive and more focused on non-routine tasks that require complex thinking, such as brainstorming and problem-solving—although automation will lighten the load of those tasks a little bit.

It’s also likely that entirely new jobs will emerge as automation becomes a critical aspect of doing business. Technology isn’t entirely self-sustaining (yet); it requires humans to build, deploy, and maintain it.

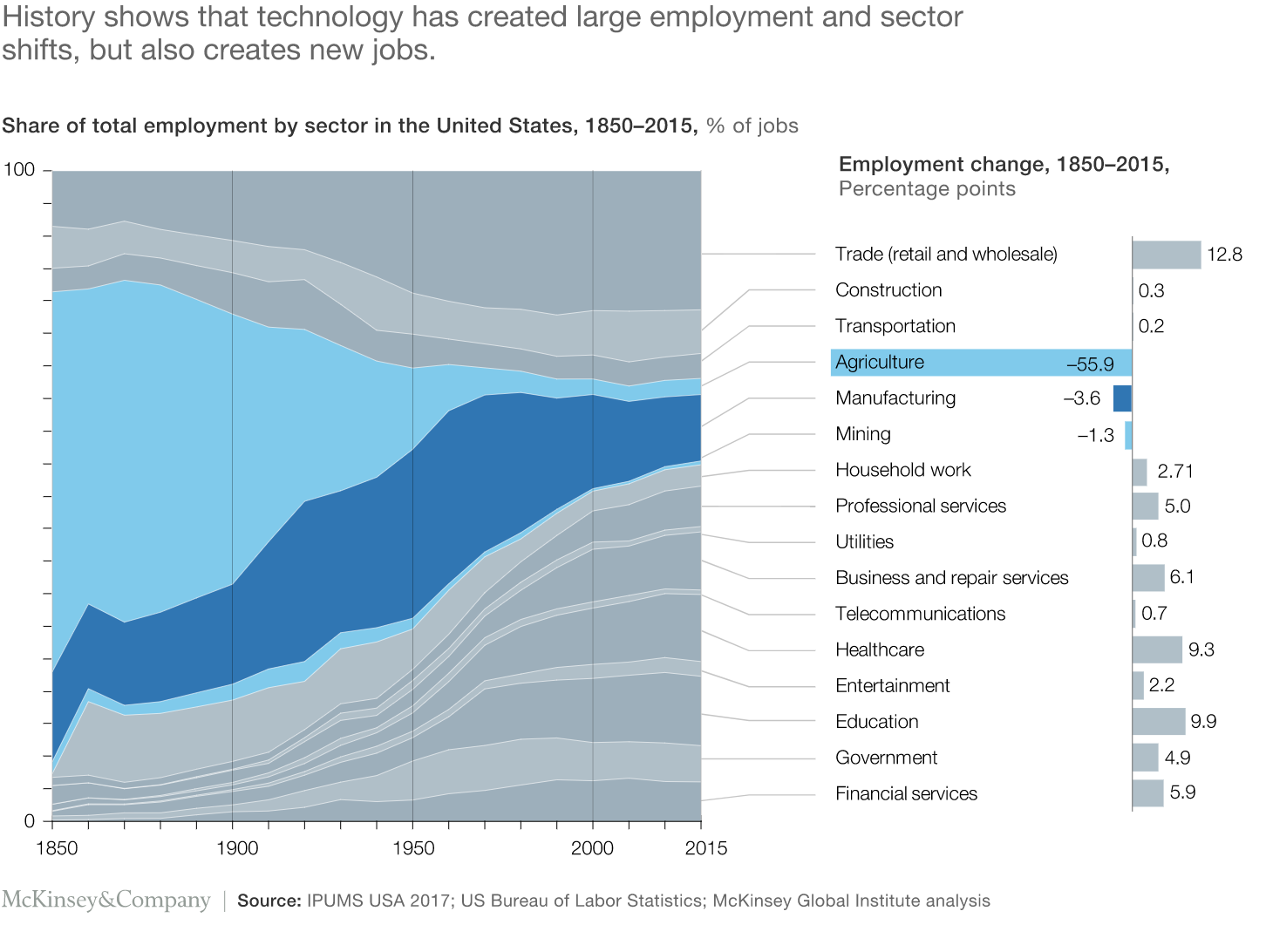

A good analogy here is the invention of the car. As automobiles became more popular, professions like “stagecoach driver” ceased to exist, but mechanics became a thing, and people moved into that profession. (If you want to be real nerdy, this graph from McKinsey does a good job illustrating how historically, labor markets have coped with technological disruption.)

Graph from McKinsey

The WEF predicts that, though technologies like automation and AI will displace 75 million jobs globally by 2022, they’ll also create 133 million new ones. This estimate is fairly conservative, too; a McKinsey analysis based on historical precedent estimates that 8-9% of 2030’s labor supply will be in roles that don’t currently exist.

Automation is a learnable, in-demand skill

In the face of these broad economic changes, your best bet is to take the Boy-Scout-motto-turned-Lion-King-song to heart: be prepared.

In advanced economies like the U.S. and Germany, up to one-third of the workforce might need to learn new skills and find new occupations by 2030 thanks to automation. So upskilling now may be your best bet to avoid being out of work later.

Upskilling can take lots of forms, but some common tips include getting better at working with data, learning a programming language, and keeping up with best tech practices for your field.

In fact, lots of companies like AT&T are getting serious about digital literacy and upskilling, because building and retaining talent might be a better investment over the long-term. It’s worth investigating whether your current employer offers similar resources.

As I mentioned earlier, there’s also a specific dearth of automation and AI talent. But there are also more accessible ways to automate work than ever before. You don’t have to be a tech wizard to use a platform like Zapier, which lets you build automated workflows with clicks instead of code.

Mastering a tool like Zapier can be a great way to upskill and stay competitive—not only will you improve your own efficiency, but you can add value to your organization as it tries to scale its use of automation.

Ultimately, the consensus is there will be some economic growing pains as automation scales. These will primarily affect low- and middle-skill workers. (In fact, research suggests that most of the economic losses from automation come from long-term unemployment.)

But it won’t be as bad as many headlines suggest, and there are ways to upskill so you can keep competing.

So no, robots likely won’t take your job, but they’ve probably already changed it.

Read more: zapier.com